- بازدید نمایندگان شیلات ایران از موج شکن بندر کنگ اسفند 1402

- دعا در دین اسلام و ادیان دیگر

- مشاورسازه های دریایی و معادن و زمین شناس

- سوابق مهندس محمدرضا آب راههRecords of Engineer mohammadreza Abraheh

- معرفی نرم افزارهای کاربردی در معدن

- قلعه پرتغالی ها در بندر کنگ

- موج شکن بندر کنگ شیلات ایران محمدرضا آب راهه

- میکاشیست و اسپیکولاریت مشخصات شهاب سنگCharacteristics of the meteorite& micaschist and specularite

- بازدید نمایندگان محترم شیلات ایران و شیلات هرمزگان از بندر کنگ

- Meteorite شهاب سنگ

آخرین مطالب

امکانات وب

Meteorite شهاب سنگ

Size

Meteorites vary in size from a few millimetres across to several feet in diameter. The largest known individual meteorite, Hoba (iron, Namibia), is shown here with a collection of tiny Holbrook (chondrite, Arizona) specimens. Hoba measures just under 9 feet (2.7 metres) wide, while the Holbrook pieces measure up to 1 centimetre (1 inch = 2.5 centimetres).

اندازه اندازه شهاب سنگ ها از چند میلی متر تا چند فوت قطر متفاوت است. بزرگترین شهاب سنگ منفرد شناخته شده، هوبا (آهن، نامیبیا)، در اینجا با مجموعه ای از نمونه های کوچک هالبروک (کندریت، آریزونا) نشان داده شده است. ابعاد هوبا کمی کمتر از 9 فوت (2.7 متر) عرض دارد، در حالی که قطعات هالبروک تا 1 سانتی متر (1 اینچ = 2.5 سانتی متر) اندازه دارند.

Holbrook. Photo: L. Garvie/BCMS Hoba. Image credit: Eugen Zibisco

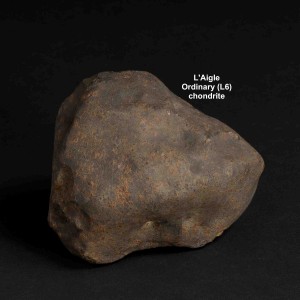

Shape

Meteorites are rarely round in shape. They are typically irregular, with rounded edges.

L’Aigle; chondrite. Photo © ASU/BCMS.

Petersburg, eucrite. Photo © ASU/BCMS.

شکل شهاب سنگ ها به ندرت شکل گرد دارند. آنها معمولاً نامنظم و با لبه های گرد هستند.

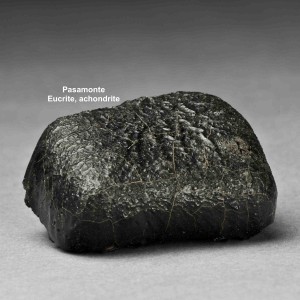

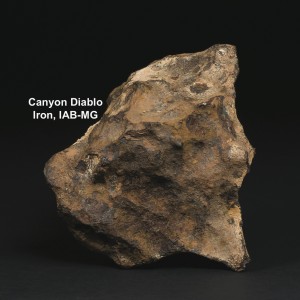

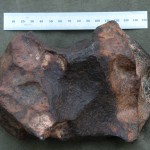

Color

The surface of a freshly fallen meteorite will appear black and shiny due to the presence of a “fusion crust,” the result of frictional heating and abrasion (or ablation) of the outer surface of the rock as it passes through the Earth’s atmosphere (see Pasamonte, below). The longer a meteorite has been on Earth, however, the more the fusion crust wears away, leaving the meteorite a rusty brown color (see Canyon Diablo, below).

Pasamonte, eucrite. Photo © ASU/BCMS. Canyon Diablo, iron. Photo © ASU/BCMS.

رنگ سطح یک شهاب سنگ تازه سقوط کرده سیاه و براق به نظر می رسد به دلیل وجود یک "پوسته همجوشی"، که نتیجه گرمایش اصطکاکی و سایش (یا فرسایش) سطح بیرونی سنگ هنگام عبور از جو زمین است (نگاه کنید به Pasamonte، زیر). با این حال، هر چه مدت زمان طولانیتری یک شهابسنگ روی زمین باشد، پوسته همجوشی بیشتر از بین میرود و رنگ قهوهای زنگزده شهابسنگ باقی میماند

Surface

While most meteorites have a smooth surface with no holes, some meteorites exhibit thin flow lines or thumbprint-like features called regmaglypts. Flow lines are cooled streaks of once-molten fusion crust. Regmaglypts are likely caused by the severe melting and abrasion of the components of the meteorite as it enters the Earth’s atmosphere.

Krähenberg, chondrite. Photo LoKiLeCh.Close-up of Bruno, iron. Photo © ASU/BCMS.

سطح در حالی که بیشتر شهابسنگها دارای سطح صاف و بدون سوراخ هستند، برخی از شهابسنگها خطوط جریان نازکی یا ویژگیهای اثر انگشت مانندی به نام رگگالیپت از خود نشان میدهند. خطوط جریان رگه های سرد شده از پوسته همجوشی یکبار مذاب هستند. رگماگلیپت ها احتمالاً ناشی از ذوب شدن و سایش شدید اجزای شهاب سنگ در هنگام ورود به جو زمین است.

Weight

In general, meteorites are heavier than Earth rocks of the same size because they have a higher nickel-iron content. Naturally-occurring Earth rocks are usually poor in metals, particularly nickel, in comparison to meteorites. The softball-sized iron meteorite (Losttown) on the left weighs over 5.5 pounds, while the large, regmaglypted iron on the right (Henbury) weighs over 282 pounds, and is under 24 inches long at its widest point!

Losttown, iron. Photo © ASU/BCMS.Henbury, iron. Photo © ASU/BCMS.

وزن به طور کلی، شهابسنگها از سنگهای هماندازه زمین سنگینتر هستند، زیرا محتوای نیکل-آهن بیشتری دارند. سنگ های طبیعی زمین معمولاً در مقایسه با شهاب سنگ ها از نظر فلزات، به ویژه نیکل، ضعیف هستند. شهاب سنگ آهنی به اندازه سافت بال (Losttown) در سمت چپ بیش از 5.5 پوند وزن دارد، در حالی که آهن بزرگ و رنگی در سمت راست (هنبری) بیش از 282 پوند وزن دارد و در عریض ترین نقطه آن کمتر از 24 اینچ طول دارد!

Interior

Most stony meteorites, especially ordinary chondrites (the most common type of meteorite recovered on Earth) will exhibit tiny metallic flecks on a broken, cut, or polished surface. In addition, most stony meteorites will exhibit small round chondrules. This section of Mezö-Madaras measures ~4 inches.

داخلی بیشتر شهابسنگهای سنگی، بهویژه کندریتهای معمولی (شایعترین نوع شهابسنگهای کشفشده در زمین) لکههای فلزی ریز روی سطحی شکسته، بریده یا صیقلی نشان میدهند. علاوه بر این، بیشتر شهابسنگهای سنگی غضروفهای گرد کوچکی را نشان میدهند. اندازه این بخش از Mez-Madaras ~ 4 اینچ است.

Mezö-Madaras, chondrite. Photo © ASU/BCMS.

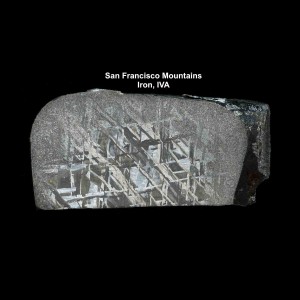

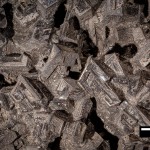

As their name implies, iron meteorites consist almost entirely of metal. The distinctive Widmanstätten pattern (named for Count Alois von Beckh Widmanstätten, director of the Austrian Imperial Porcelain Works, in 1808), seen on some etched iron meteorite surfaces, is created by the interlocking crystal structure of two nickel-iron alloys (kamacite and taenite).

همانطور که از نام آنها پیداست، شهاب سنگ های آهنی تقریباً به طور کامل از فلز تشکیل شده اند. الگوی متمایز Widmansttten (به نام کنت Alois von Beckh Widmansttten، مدیر کارهای چینی امپراتوری اتریش، در سال 1808) که بر روی برخی از سطوح شهاب سنگ آهن حکاکی شده دیده می شود، توسط ساختار کریستالی به هم پیوسته دو آلیاژ نیکل-آهن (taenitete) ایجاد شده است. ).

Muonionalusta, iron. Photo © ASU/BCMS.San Francisco Mountains, iron. Photo ASU/BCMS

Stony-iron meteorites contain approximately 50% silicate and 50% metal which, in some pallasites, may show Widmanstätten lines after etching.

شهابسنگهای سنگی-آهنی حاوی تقریباً 50 درصد سیلیکات و 50 درصد فلز هستند که در برخی از پالازیتها، ممکن است خطوط Widmansttten را پس از حکاکی نشان دهند.

Seymchan, pallasite. Photo © ASU/BCMS. Hainholz, mesosiderite. Photo © ASU/BCMS.

Magnetism

A magnet will be attracted to most meteorites, even stony meteorites, due to their high iron and nickel content.

مغناطیس یک آهنربا به دلیل محتوای بالای آهن و نیکل، جذب اکثر شهاب سنگ ها، حتی شهاب سنگ های سنگی می شود.

This causes intense heat and pressure to act on the surface of the rock. The outside of the meteorite vaporizes, and a thin molten layer forms on the outside of the rock. The body is usually broken up by extreme ram pressures, and the fragments begin to ablate as well.

If any rocks do survive the passage, they almost always bear some scars. As the fragments are slowed down by the atmosphere, their surfaces begin to cool. The last molten material on the rock’s surface cools and solidifies on the outside of the meteorite, forming a “fusion crust.” This layer is usually fairly smooth, but is not the polished texture of a water-worn pebble.

Freshly-fallen meteorites as found:

As you can see, the ~black outer layer is usually ~smooth, but finely textured. While meteorites themselves almost never contain any bubbles, the outer layer of crust can exhibit small bubbles (but usually doesn’t). Note that none of these rocks has actually melted through. Inside, they’re still grainy rocks, for the most part. See here, #2 for a little more information on what happens as meteorites fall to Earth.

2) Most meteorites start out on a gradient from ~white to ~black inside. Here are a few examples:

Freshly fallen meteorites, naturally broken and cut:

رر

رر

The above album contains freshly-fallen meteorites. Some are broken, others are cut. Most of the broken stones fragmented in the atmosphere or when they landed on a hard surface. As you can see, they range from ~light grey to black inside. There are a few other details you might have noticed…a few have started to oxidize (3rd, 6th images). More on that later.

There are also a few exceptions to the grey-black gradient — namely with pale green meteorites made mostly of olivine or pyroxene. However, these meteorites are exceedingly rare, and only a dozen or so have been seen to fall in recorded history. So, we’ll skip the details on diogenites and visually ~similar meteorites.

So, right after they fall, most meteorites have a black crust on the outside, and they range from ~white to ~black on the inside. But most meteorites that are found didn’t fall recently. Most meteorites found on Earth have spent thousands of years here, just waiting to be picked up. What do those meteorites look like? Well…

Weathered meteorites

~95% of meteorites contain between ~10 and ~20% metallic iron when they fall. This iron begins to rust after landing on Earth: a freshly fallen meteorite won’t be rusty, but ~95% of meteorites will begin to show at least minor oxidation within weeks to months. After a few decades, they’ll be ~thoroughly rusty. Most meteorites on Earth fell at least hundreds if not thousands of years ago, so a rusty color is fairly typical of most meteorites:

So…rusty rocks. If you look carefully, you can see that some still have some smooth fusion crust, although it has been weathered to brown or has been mostly chipped off in many cases. The textures are important — note that the older fusion crust is uniformly textured even on concave surfaces: that’s uncommon for terrestrial rocks. Weathering on usually Earth starts from the edges/corners, rounding those off first.

Other Defining Characteristics

There are a few other kinds of details you can look for. ~90+% of all meteorites are “stony” meteorites. This kind of meteorite usually contains features called chondrules.

What are chondrules? We’re not sure exactly how they formed, but we know they date back to the earliest days of our solar system, 4.56 billion years ago. In a nutshell — they’re small spherical droplets of rock, usually about a millimeter in diameter. They range from 0.1 mm or smaller to ~1 cm across. In rare cases they can be larger, but they’re usually 1 mm or so. Here are some examples of chondrules in cut meteorites:

چند نوع دیگر از جزئیات وجود دارد که می توانید به دنبال آن باشید. 90+٪ از همه شهاب سنگ ها شهاب سنگی هستند. این نوع شهاب سنگ معمولاً دارای ویژگی هایی به نام غضروف است. کندرول چیست؟ ما دقیقاً مطمئن نیستیم که آنها چگونه شکل گرفته اند، اما می دانیم که قدمت آنها به اولین روزهای منظومه شمسی ما یعنی 4.56 میلیارد سال پیش برمی گردد. به طور خلاصه - آنها قطرات کروی کوچکی از سنگ هستند که معمولاً حدود یک میلی متر قطر دارند. عرض آنها از 0.1 میلی متر یا کوچکتر تا 1 سانتی متر متغیر است. در موارد نادر میتوانند بزرگتر باشند، اما معمولاً ۱ میلیمتر یا بیشتر هستند. در اینجا چند نمونه از کندرول ها در شهاب سنگ های بریده آورده شده است:

~90% of meteorites will look something like this when cut. When looking for meteorites, this is what you are most likely to find. Note that in many of them the chondrules are only faintly visible, if at all. This is common. Also, note that many of these stones exhibit visible metal flakes when cut. A more oxidized meteorite might not have any of these left, but a polished stony meteorite will almost always still have some of these. Flecks of specular hematite in terrestrial rocks can look similar, but appear darker, and less like native metal.

Also – shock veins. When asteroids collide with each other in space, they can do so at thousands of miles per hour. Some become truly broken up and brecciated, while others get only a few thin, usually black, veins of melt. Here are some examples:

90 درصد از شهابسنگها هنگام برش چیزی شبیه این به نظر میرسند. وقتی به دنبال شهاب سنگ می گردید، این همان چیزی است که به احتمال زیاد پیدا خواهید کرد. توجه داشته باشید که در بسیاری از آنها غضروف ها فقط به صورت ضعیف قابل مشاهده هستند. این رایج است. همچنین، توجه داشته باشید که بسیاری از این سنگ ها هنگام برش، ورقه های فلزی قابل رویت را نشان می دهند. شهابسنگهای اکسید شدهتر ممکن است هیچکدام از اینها را نداشته باشند، اما یک شهابسنگ سنگی صیقلی تقریباً همیشه برخی از اینها را خواهد داشت. تکههای هماتیت اسپکولار در سنگهای زمینی میتوانند شبیه به نظر برسند، اما تیرهتر و کمتر شبیه فلز بومی به نظر میرسند. همچنین – رگهای شوک. هنگامی که سیارک ها در فضا با یکدیگر برخورد می کنند، می توانند این کار را با سرعت هزاران مایل در ساعت انجام دهند. برخی از آنها واقعاً شکسته و برش می شوند، در حالی که برخی دیگر فقط چند رگه نازک، معمولاً سیاه، مذاب دارند. در اینجا چند نمونه آورده شده است:

Not all meteorites have these, but they can be a good indicator. Some terrestrial rocks can look similar, but they’re not too common.

Stony meteorites without chondrules are very rare, and they usually look very much like terrestrial igneous rocks on the inside. The only good identifying features of these types of meteorites are shock veins and fusion crust. These meteorites rarely oxidize over time. In 15 years of hunting in good desert terrain, we have found three such meteorites. They’re so rare — and usually so hard to identify — that it’s probably not worth spending time looking for them until you know quite a bit about meteorites. Here are some examples.

ron and stony-iron meteorites are very rare, but are easy to recognize. These classes make up ~2% of meteorites, and they are mostly metallic.

همه شهاب سنگ ها اینها را ندارند، اما می توانند شاخص خوبی باشند. برخی از سنگ های زمینی ممکن است شبیه به هم به نظر برسند، اما چندان رایج نیستند. شهابسنگهای سنگی بدون غضروف بسیار نادر هستند و معمولاً در داخل بسیار شبیه سنگهای آذرین زمینی هستند. تنها ویژگی شناسایی خوب این نوع شهاب سنگ ها رگه های شوک و پوسته همجوشی است. این شهاب سنگ ها به ندرت در طول زمان اکسید می شوند. در 15 سال شکار در زمین های بیابانی خوب، سه شهاب سنگ از این دست پیدا کرده ایم. آنها به قدری نادر هستند - و معمولاً شناسایی آنها بسیار دشوار است - که احتمالاً ارزش وقت گذاشتن برای جستجوی آنها را ندارد تا زمانی که کمی در مورد شهاب سنگ ها بدانید. در اینجا چند نمونه آورده شده است. شهاب سنگ های آهنی و سنگی-آهنی بسیار نادر هستند، اما به راحتی قابل تشخیص هستند. این طبقات حدود 2% از شهاب سنگ ها را تشکیل می دهند و بیشتر فلزی هستند.

All of the above meteorites would be very strongly attracted to a magnet. As much as a piece of solid iron. They’re typically fairly easy to identify. Note: many have deep indentations in their surfaces, but no “bubbles.”

But be careful — many terrestrial rocks also contain (magnetic) iron, and people have been concentrating iron to make tools (and thus, slag), for thousands of years. Most iron-bearing, magnetic rocks on Earth are from Earth.

Which raises an important idea: if hunting for meteorites, it is very important that you be familiar with characteristics that meteorites do not have. Many meteorites have been found by people familiar with rocks, their surroundings, their farms, etc., who noticed something out of place. They didn’t know what meteorites looked like; they just noticed that a rock didn’t look like the other ones around.

همه شهابسنگهای فوق به شدت جذب یک آهنربا میشوند. به اندازه یک تکه آهن جامد. شناسایی آنها معمولاً نسبتاً آسان است. توجه: بسیاری از آنها دارای فرورفتگی عمیق در سطوح خود هستند، اما "حباب" ندارند. اما مراقب باشید - بسیاری از سنگهای زمینی نیز حاوی آهن (مغناطیسی) هستند، و مردم برای هزاران سال آهن را برای ساختن ابزار (و بنابراین، سرباره) متمرکز میکنند. بیشتر سنگهای آهندار و مغناطیسی روی زمین از زمین هستند. که ایده مهمی را مطرح میکند: در صورت شکار شهابسنگ، بسیار مهم است که با ویژگیهایی که شهابسنگها ندارند آشنا باشید. شهابسنگهای زیادی توسط افرادی که با صخرهها، محیط اطراف، مزارعشان و غیره آشنا هستند، پیدا شدهاند که متوجه چیزی نابجا شدهاند. آنها نمی دانستند شهاب سنگ ها چه شکلی هستند. آنها فقط متوجه شدن د که یک سنگ شبیه سنگ های اطراف نیست.

Most of the rocks in this image are dark / rusty brown and slightly magnetic. Can you spot the meteorite? Click on the image for a closer look. Click here for a spoiler.

Knowing what meteorites look like is only half of the battle. If you want to find a meteorite, a general understanding of geology is extremely helpful. If you learn as much as you can about different rocks and how they form, you will be much better equipped to identify rocks (and meteorites) in the field.

بیشتر سنگ های این تصویر قهوه ای تیره / زنگ زده و کمی مغناطیسی هستند. آیا می توانید شهاب سنگ را تشخیص دهید؟ برای مشاهده دقیق روی تصویر کلیک کنید. برای دریافت اسپویلر، اینجا را کلیک کنید. دانستن اینکه شهاب سنگ ها چگونه به نظر می رسند، تنها نیمی از نبرد است. اگر می خواهید یک شهاب سنگ پیدا کنید، درک کلی زمین شناسی بسیار مفید است. اگر تا آنجا که می توانید درباره سنگ های مختلف و نحوه تشکیل آنها بیاموزید، برای شناسایی سنگ ها (و شهاب سنگ ها) در میدان بسیار مجهزتر خواهید بود.

Common Meteor-Wrongs

Here are some photographs of pieces of a very common meteor-wrong — man-made slag. These are not meteorites:

Image credits: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12.

Note the bubbles, large, bubbly flow features, and “skin” that often forms on the surface of pooling slag. Meteorites don’t “melt-through” when they’re coming through the atmosphere, so if you see characteristics that suggest your rock was literally flowing or molten like lava, you know it’s not a meteorite. The molten surface of slag is very different in texture from a fusion crust (compare to other images above), and there are usually large bubbles below this smooth skin.

One or two of the above specimens don’t look half bad. The 7th image in particular isn’t a bad wrong, but the few included flint fragments suggest it’s not a meteorite — a few pieces of unmelted rock appear to have been incorporated into the molten metal. Small amounts of sand and rock can adhere to a rusting meteorite though; this can give a grossly similar appearance, so be careful. I’d probably suggest cutting a specimen if in doubt. If you see vesicles or vugs, you’re almost certainly out of luck.

Here’s a great page by Helmut Föll on furnace bloom, how it’s made, and why it looks how it does. And a stable PDF of the page, saved May 2018.

به حبابها، ویژگیهای جریان حبابدار بزرگ و «پوست» که اغلب روی سطح سرباره ادغامشده تشکیل میشود توجه کنید. شهابسنگها زمانی که از جو عبور میکنند «ذوب نمیشوند»، بنابراین اگر ویژگیهایی را مشاهده کردید که نشان میدهد سنگ شما به معنای واقعی کلمه جاری بوده یا مانند گدازه مذاب است، میدانید که این یک شهابسنگ نیست. سطح مذاب سرباره از نظر بافت با پوسته همجوشی بسیار متفاوت است (در مقایسه با سایر تصاویر بالا)، و معمولاً حباب های بزرگی در زیر این پوسته صاف وجود دارد. یک یا دو نمونه از نمونه های بالا نیمه بد به نظر نمی رسند. به طور خاص، تصویر هفتم اشتباه بدی نیست، اما چند تکه سنگ چخماق موجود در آن نشان می دهد که این یک شهاب سنگ نیست - به نظر می رسد چند تکه سنگ ذوب نشده در فلز مذاب ادغام شده است. هر چند مقدار کمی شن و سنگ می تواند به یک شهاب سنگ زنگ زده بچسبد. این می تواند ظاهری کاملاً مشابه بدهد، بنابراین مراقب باشید. من احتمالاً پیشنهاد می کنم در صورت شک، نمونه ای را برش دهید. اگر وزیکول یا وگ می بینید، تقریباً مطمئناً شانس ندارید. در اینجا یک صفحه عالی از هلموت فول در مورد شکوفایی کوره، نحوه ساخت آن، و چرایی ظاهر آن وجود دارد. و یک پیدیاف پایدار صفحه، ذخیرهشده در می ۲۰۱۸.

Another common wrong — manganese slag (source):

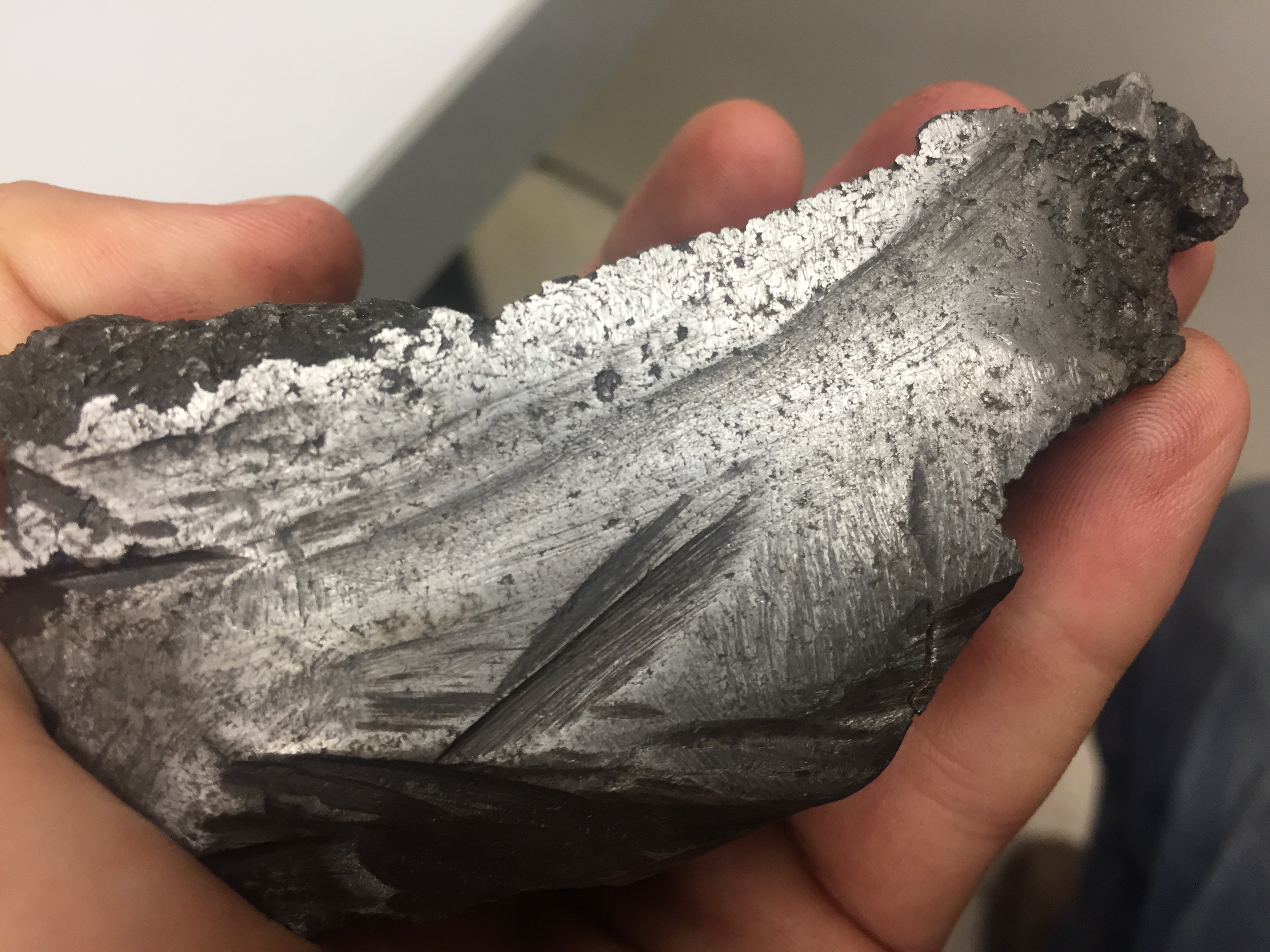

Manganese slag feels quite dense, is often ~a little magnetic, looks silvery/metallic when polished, and has a rusty-to-black exterior (that often rubs off on your fingers as a fine black dust). How can you tell it from a meteorite? The surface of manganese slag specimens is often quite rough, but not very rusty: that fine black dust that’s hard to get off of your hands is manganese oxide, and it’s different from typical iron ‘rust.’ And while manganese is dense/feels like metal, an iron meteorite would be made of ~90% iron, and would be very strongly attracted to a magnet. All metallic meteorites are strongly magnetic. Most manganese slag isn’t very magnetic. Some manganese slag contains a decent amount of iron, so you have to be careful. It usually still oxidizes in the same odd way, though.

Why can’t a meteorite be made mostly of manganese, aluminum, copper, or some other metal? Earth is geologically and hydrologically one of the most active bodies in the solar system — second, perhaps, only to Jupiter’s sulfur-rich moon, Io. Complex hydrologic reactions need to take place on Earth in order for these metals to naturally precipitate, and we can be fairly certain that it’s not happening anywhere else in our Solar System. You need large amounts of liquid water to carry acids or bases in addition to extended exposure to geothermal heat to drive the kinds of chemical reactions that can concentrate, say, copper. The few bodies that have enough geologic heat to drive these kinds of reactions, like Io and Venus, are bone dry, and the few bodies with enough water to support these kinds of reactions, like Europa and Enceladus, are extremely cold. Earth is a pretty unique place in the Solar System.

Most iron meteorites formed by a very simple general sort of process: chondritic material was melted by heat from impacts or heat released by the radioactive decay of elements. The metal in most chondrites is ~85% iron, and ~15% nickel. There’s ~no natural way to concentrate large amounts of, say, manganese, copper, or other metals in such a process. You can, in rare cases, find *micron*-sized inclusions of copper and gold in highly-shocked meteorites. That’s as far as these kinds processes ever got, out in space.

Conversely, these metals have been concentrated by people, on Earth, from prehistoric times and into the present. Most pieces of metal brought into labs as possible meteorites are industrial waste. Which makes sense — people have been refining different metals for thousands of years, and leaving the trash just about everywhere. I’ve found slag on mountainsides, in farm fields, and poking through pine needles in remote forests. It’s everywhere.

Here’s a good example.

Some folks brought this piece of metal into UCLA in 2018. They managed to cut it off of a 2-3 tonne ~rounded mass of iron they found in a remote part of the Mojave desert. The photos of it looked kind of like a meteorite, but the cut surface looks…dendritic. And UCLA’s SEM showed that the metal was pure iron with trace amounts of silicon, carbon, etc.

Some folks brought this piece of metal into UCLA in 2018. They managed to cut it off of a 2-3 tonne ~rounded mass of iron they found in a remote part of the Mojave desert. The photos of it looked kind of like a meteorite, but the cut surface looks…dendritic. And UCLA’s SEM showed that the metal was pure iron with trace amounts of silicon, carbon, etc.

It was cast iron. I have no idea how it got there, but it is what it is.

Here’s another odd example.

برخی از مردم این قطعه فلز را در سال 2018 به UCLA آوردند. آنها موفق شدند آن را از یک توده 2 تا 3 تنی گرد آهنی که در قسمتی دورافتاده از صحرای موهاوه پیدا کردند، جدا کنند. عکس های آن به نوعی شبیه یک شهاب سنگ به نظر می رسید، اما سطح بریده شده به نظر می رسد ... دندریتی است. و SEM UCLA نشان داد که این فلز آهن خالص با مقادیر کمی سیلیکون، کربن و غیره است. چدن بود. من نمی دانم چگونه به آنجا رسیده است، اما همین چیزی است که هست. در اینجا یک مثال عجیب دیگر است.

Someone sent me photos of this thing in early 2019, claiming that it was a meteorite. The large curved broken faces pretty much ruled that out. It was a piece of brittle, granular metal. Slag often breaks that way. Meteorites ~never do.

They said that a portable XRF gun analysis had showed that it was comprised of 99.9% iron. That’s really pure iron. More pure than has ever been found naturally on Earth or anywhere else. So pure that it must have been refined artificially…

Although the analysis actually was ~98.7% iron, with trace amounts of manganese and chromium, and around 0.1% nickel. Which is pretty typical iron slag. The person later listed it on eBay for $100,000 as a specimen that “baffled all experts.” Even though nothing suggested it was a meteorite.

If you have a strange piece of metal, or a metallic rock, and it’s not strongly attracted to a magnet, it’s not a meteorite. There are no exceptions. If you have something metallic, but not magnetic, it’s almost certainly man-made. If not, it’s still terrestrial (i.e. a copper nugget).

And if you find something that’s iron, but contains less than ~4% nickel, it’s probably man made, and definitely not a meteo

شخصی در اوایل سال 2019 عکس هایی از این چیز را برای من فرستاد و ادعا کرد که این یک شهاب سنگ است. صورت های شکسته منحنی بزرگ تا حد زیادی این امر را رد می کرد. این یک قطعه فلزی شکننده و دانهدار بود. سرباره اغلب از این طریق می شکند. شهاب سنگ ها هرگز انجام نمی دهند. آنها گفتند که تجزیه و تحلیل اسلحه XRF قابل حمل نشان داده است که از 99.9٪ آهن تشکیل شده است. این واقعاً آهن خالص است. خالص تر از همیشه به طور طبیعی روی زمین یا هر جای دیگری یافت شده است. آنقدر خالص که باید به صورت مصنوعی تصفیه شده باشد… اگرچه تجزیه و تحلیل در واقع 98.7٪ آهن، با مقادیر کمی منگنز و کروم، و حدود 0.1٪ نیکل بود. که سرباره آهن بسیار معمولی است. آن شخص بعداً آن را در eBay به قیمت 100000 دلار به عنوان نمونه ای فهرست کرد که "همه کارشناسان را گیج کرد". با وجود اینکه هیچ چیز نشان نمی داد که این یک شهاب سنگ است. اگر یک قطعه فلزی عجیب یا یک سنگ فلزی دارید و به شدت جذب آهنربا نمی شود، این یک شهاب سنگ نیست. هیچ استثنایی وجود ندارد. اگر چیزی فلزی دارید، اما مغناطیسی نیست، تقریباً مطمئناً ساخته دست بشر است. اگر نه، هنوز زمینی است (یعنی یک قطعه مس). و اگر چیزی پیدا کردید که آهن است، اما حاوی کمتر از 4٪ نیکل است، احتمالاً ساخته دست بشر است و قطعاً یک شهاب سنگ نیست.

منبع :

Source :

https://meteoritegallery.com/

ساختار شکست کار چیست (WBS)...برچسب : نویسنده : abraheh بازدید : 149